OOP: Extends VS Implements

OOP: Extends VS Implements (OverView)

A struct in golang can be compared to a class in Object Oriented Languages. In GoLang, your type satisfies an interface after all the methods have been implemented.

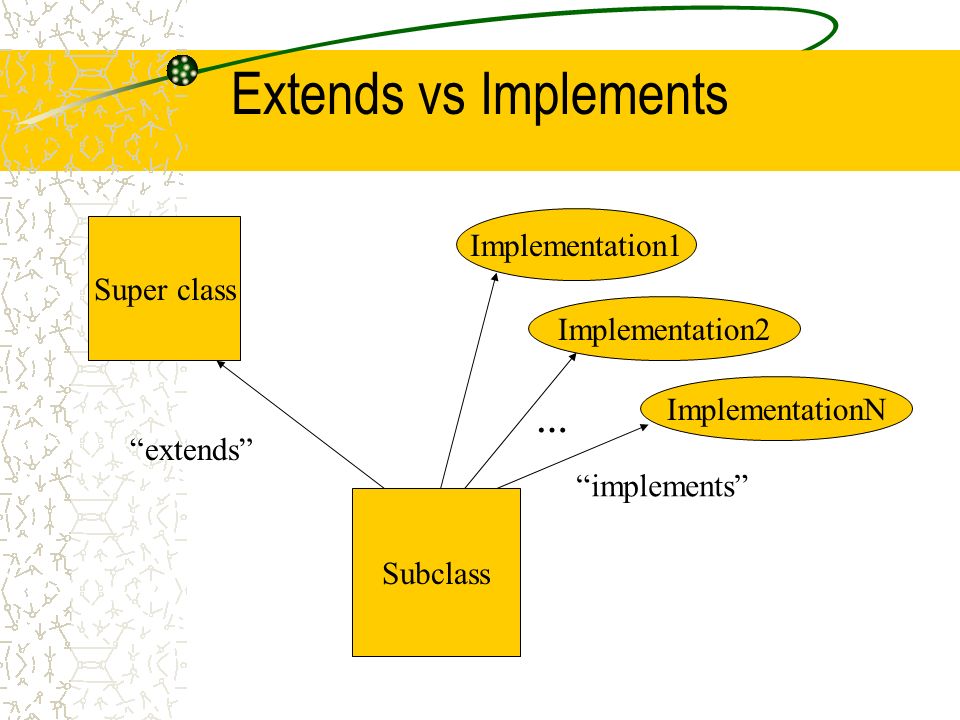

Inheritance is an important pillar of OOP(Object Oriented Programming). It is the mechanism in Java by which one class is allowed to inherit the features(fields and methods) of another class. There are two main keywords, “extends” and “implements” which are used in Java for inheritance. In this article, the difference between extends and implements is discussed.

Before getting into the differences, lets first understand in what scenarios each of the keywords are used.

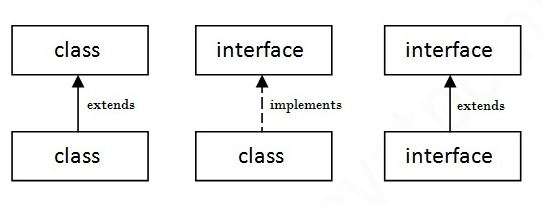

Extends: In Java, the extends keyword is used to indicate that the class which is being defined is derived from the base class using inheritance. So basically, extends keyword is used to extend the functionality of the parent class to the subclass. In Java, multiple inheritances are not allowed due to ambiguity. Therefore, a class can extend only one class to avoid ambiguity.

Implements: In Java, the implements keyword is used to implement an interface. An interface is a special type of class which implements a complete abstraction and only contains abstract methods. To access the interface methods, the interface must be “implemented” by another class with the implements keyword and the methods need to be implemented in the class which is inheriting the properties of the interface. Since an interface is not having the implementation of the methods, a class can implement any number of interfaces at a time.

-

Note: A class can extend a class and can implement any number of interfaces simultaneously.

-

Note: An interface can extend any number of interfaces at a time.

The following table explains the difference between the extends and interface:

| EXTENDS | IMPLEMENTS | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | By using “extends” keyword a class can inherit another class, or an interface can inherit other interfaces | By using “implements” keyword a class can implement an interface |

| 2. | It is not compulsory that subclass that extends a superclass override all the methods in a superclass. | It is compulsory that class implementing an interface has to implement all the methods of that interface. |

| 3. | Only one superclass can be extended by a class. | A class can implement any number of an interface at a time |

| 4. | Any number of interfaces can be extended by interface. | An interface can never implement any other interface |

OOP: Extends VS Implements (Differences)

Generally implements used for implementing an interface and extends used for extension of base class behaviour or abstract class.

extends: A derived class can extend a base class. You may redefine the behaviour of an established relation. Derived class “is a” base class type

implements: You are implementing a contract. The class implementing the interface “has a” capability.

With java 8 release, interface can have default methods in interface, which provides implementation in interface itself.

public class ExtendsAndImplementsDemo{

public static void main(String args[]){

Dog dog = new Dog("Tiger",16);

Cat cat = new Cat("July",20);

System.out.println("Dog:"+dog);

System.out.println("Cat:"+cat);

dog.remember();

dog.protectOwner();

Learn dl = dog;

dl.learn();

cat.remember();

cat.protectOwner();

Climb c = cat;

c.climb();

Man man = new Man("Ravindra",40);

System.out.println(man);

Climb cm = man;

cm.climb();

Think t = man;

t.think();

Learn l = man;

l.learn();

Apply a = man;

a.apply();

}

}

abstract class Animal{

String name;

int lifeExpentency;

public Animal(String name,int lifeExpentency ){

this.name = name;

this.lifeExpentency=lifeExpentency;

}

public void remember(){

System.out.println("Define your own remember");

}

public void protectOwner(){

System.out.println("Define your own protectOwner");

}

public String toString(){

return this.getClass().getSimpleName()+":"+name+":"+lifeExpentency;

}

}

class Dog extends Animal implements Learn{

public Dog(String name,int age){

super(name,age);

}

public void remember(){

System.out.println(this.getClass().getSimpleName()+" can remember for 5 minutes");

}

public void protectOwner(){

System.out.println(this.getClass().getSimpleName()+ " will protect owner");

}

public void learn(){

System.out.println(this.getClass().getSimpleName()+ " can learn:");

}

}

class Cat extends Animal implements Climb {

public Cat(String name,int age){

super(name,age);

}

public void remember(){

System.out.println(this.getClass().getSimpleName() + " can remember for 16 hours");

}

public void protectOwner(){

System.out.println(this.getClass().getSimpleName()+ " won't protect owner");

}

public void climb(){

System.out.println(this.getClass().getSimpleName()+ " can climb");

}

}

interface Climb{

public void climb();

}

interface Think {

public void think();

}

interface Learn {

public void learn();

}

interface Apply{

public void apply();

}

class Man implements Think,Learn,Apply,Climb{

String name;

int age;

public Man(String name,int age){

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

}

public void think(){

System.out.println("I can think:"+this.getClass().getSimpleName());

}

public void learn(){

System.out.println("I can learn:"+this.getClass().getSimpleName());

}

public void apply(){

System.out.println("I can apply:"+this.getClass().getSimpleName());

}

public void climb(){

System.out.println("I can climb:"+this.getClass().getSimpleName());

}

public String toString(){

return "Man :"+name+":Age:"+age;

}

}

Important points to understand:

-

Dog and Cat are animals and they extended remember() and protectOwner() by sharing name, lifeExpentency from Animal Cat can climb() but Dog does not. Dog can think() but Cat does not. These specific capabilities are added to Cat and Dog by implementing that capability.

-

Man is not an animal but he can Think,Learn,Apply,Climb

By going through these examples, you can understand that Unrelated classes can have capabilities through interface but related classes override behaviour through extension of base classes.

OOP: Extends VS Implements (Use Cases)

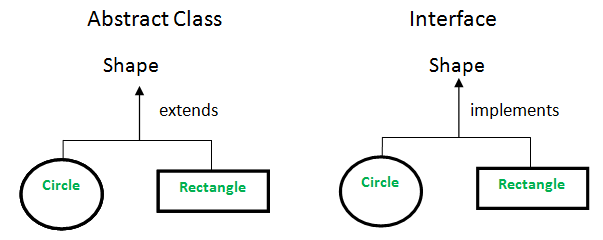

Consider using abstract classes if:

-

You want to share code among several closely related classes.

-

You expect that classes that extend your abstract class have many common methods or fields, or require access modifiers other than public (such as protected and private).

-

You want to declare non-static or non-final fields.

Consider using interfaces if:

-

You expect that unrelated classes would implement your interface. For example,many unrelated objects can implement Serializable interface.

-

You want to specify the behaviour of a particular data type, but not concerned about who implements its behaviour.

-

You want to take advantage of multiple inheritance of type.

In simple terms, I would like to use

interface: To implement a contract by multiple unrelated objects

abstract class: To implement the same or different behaviour among multiple related objects

Definations

An interface is a behavioral contract between multiple systems.

That means any class that implements an interface guarantees and must provide some implementation for all of its methods. All methods in an interface must be public and abstract.

An abstract class is prefixed by the abstract keyword in its declaration and is a guideline created for its derived concrete classes. Abstract classes must have at least one abstract method and provide the implementation for its non-abstract methods.

When to use what?

Consider using abstract classes if any of these statements apply to your situation:

-

In java application, there are some related classes that need to share some lines of code then you can put these lines of code within abstract class and this abstract class should be extended by all these related classes.

-

You can define non-static or non-final field(s) in abstract class, so that via a method you can access and modify the state of Object to which they belong.

-

You can expect that the classes that extend an abstract class have many common methods or fields, or require access modifiers other than public (such as protected and private).

Consider using interfaces if any of these statements apply to your situation:

-

It is total abstraction, All methods declared within an interface must be implemented by the class(es) that implements this interface.

-

A class can implement more than one interface. It is called multiple inheritance.

-

You want to specify the behavior of a particular data type, but not concerned about who implements its behavior.

Embedding in Go

Go doesn’t support inheritance in the classical sense; instead, in encourages composition as a way to extend the functionality of types.

Embedding is an important Go feature making composition more convenient and useful. While Go strives to be simple, embedding is one place where the essential complexity of the problem leaks somewhat.

There are three kinds of embedding in Go:

-

Structs in structs

-

Interfaces in interfaces

-

Interfaces in structs

Embedding structs in structs

type Base struct {

b int

}

type Container struct { // Container is the embedding struct

Base // Base is the embedded struct

c string

}

Instances of Container will now have the field b as well. In the spec, it’s called a promoted field. We can access it just as we’d do for c:

co := Container{}

co.b = 1

co.c = "string"

fmt.Printf("co -> {b: %v, c: %v}\n", co.b, co.c)

Methods

Embedding structs also works well with methods. Suppose we have this method available for Base:

func (base Base) Describe() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("base %d belongs to us", base.b)

}

We can now invoke it on instances of Container, as if it had this method too:

fmt.Println(cc.Describe())

To understand the mechanics of this call better, it helps to visualize Container having an explicit field of type Base and an explicit Describe method that forwards the call:

type Container struct {

base Base

c string

}

func (cont Container) Describe() string {

return cont.base.Describe()

}

The effect of calling Describe on this alternative Container is similar to our original one which uses an embedding.

This example also demonstrates an important subtlety in how methods on embedded fields behave; when Base’s Describe is called, it’s passed a Base receiver (the leftmost (…) in the method definition), regardless of which embedding struct it’s called through. This is different from inheritance in other languages like Python and C++, where inherited methods get a reference to the subclass they are invoked through. This is a key way in which embedding in Go is different from classical inheritance.

Shadowing of embedded fields

What happens if the embedding struct has a field x and embeds a struct which also has a field x? In this case, when accessing x through the embedding struct, we get the embedding struct’s field; the embedded struct’s x is shadowed.

Here’s an example demonstrating this:

type Base struct {

b int

tag string

}

func (base Base) DescribeTag() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("tag is %s", base.tag)

}

type Container struct {

Base

c string

tag string

}

func (co Container) DescribeTag() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("tag is %s", co.tag)

}

Embedding interfaces in interfaces

Embedding an interface in another interface is the simplest kind of embedding in Go, because interfaces only declare capabilities; they don’t actually define any new data or behavior for a type.

An interface can embed any number of interfaces in it as well as it can be embedded in any interface. All the methods of the embedded interface become part of the embedding interface. It is a way of creating a new interface by merging some small interfaces.

type Reader interface {

Read(p []byte) (n int, err error)

}

type Writer interface {

Write(p []byte) (n int, err error)

}

type ReadWriter interface {

Read(p []byte) (n int, err error)

Write(p []byte) (n int, err error)

}

Apart from the obvious issue of duplicating the same method declarations in several places, this hinders the readability of ReadWriter because it’s not immediately apparent how it composes with the other two interfaces. You either have to remember the exact declaration of each method by heart or keep looking back at other interfaces.

Note that there are many such compositional interfaces in the standard library; there’s io.ReadCloser, io.WriteCloser, io.ReadWriteCloser, io.ReadSeeker, io.WriteSeeker, io.ReadWriteSeeker and more in other packages. The declaration of the Read method alone would likely have to be repeated more than 10 times in the standard library. This would be a shame, but luckily interface embedding provides the perfect solution:

type ReadWriter interface {

Reader

Writer

}

In addition to preventing duplication, this declaration states intent in the clearest way possible: in order to implement ReadWriter, you have to implement Reader and Writer.

Embedding interfaces is composable and works as you’d expect. For example, given the interfaces A, B, C and D such that:

type A interface {

Amethod()

}

type B interface {

A

Bmethod()

}

type C interface {

Cmethod()

}

type D interface {

B

C

Dmethod()

}

The method set of D will consist of Amethod(), Bmethod(), Cmethod() and Dmethod().

However, suppose C were defined as:

type C interface {

A

Cmethod()

}

Generally speaking, this shouldn’t change the method set of D. However, prior to Go 1.14 this would result in an error “Duplicate method Amethod” for D, because Amethod() would be declared twice - once through the embedding of B and once through the embedding of C.

Go 1.14 fixed this and these days the new example works and just as we’d expect. The method set of D is the union of the method sets of the interfaces it embeds and of its own methods.

A more practical example comes from the standard library. The type io.ReadWriteCloser is defined as:

type ReadWriteCloser interface {

Reader

Writer

Closer

}

// But it could be defined more succinctly with:

type ReadWriteCloser interface {

io.ReadCloser

io.WriteCloser

}

Embedding interfaces in structs

An interface can be embedded in a struct as well. All the methods of the embedded interface can be called via that struct. How these methods will be called will depend upon whether the embedded interface is a named field or an unnamed/anonymous field.

-

If the embedded interface is a named field, then interface methods have to be called via the named interface name

-

If the embedded interface is unnamed/anonymous field then interface methods can be referred directly or via the interface name

At first sight, this is the most confusing embedding supported in Go. It’s not immediately clear what embedding an interface in a struct means. In this post we’ll work through this technique slowly and present several real-world examples. At the end, you’ll see that the underlying mechanics are pretty simple and the technique is useful in various scenarios.

type Fooer interface {

Foo() string

}

type Container struct {

Fooer

}

Fooer is an interface and ontainer embeds it. Recall from part 1 that an embedding in a struct promotes the embedded struct’s methods to the embedding struct. It works similarly for embedded interfaces; we can visualize it as if Container had a forwarding method like this:

func (cont Container) Foo() string {

return cont.Fooer.Foo()

}

But what does cont.Fooer refer to? Well, it’s just any object that implements the Fooer interface. Where does this object come from? It is assigned to the Fooer field of Container when the container is initialized, or later. Here’s an example:

// sink takes a value implementing the Fooer interface.

func sink(f Fooer) {

fmt.Println("sink:", f.Foo())

}

// TheRealFoo is a type that implements the Fooer interface.

type TheRealFoo struct {

}

func (trf TheRealFoo) Foo() string {

return "TheRealFoo Foo"

}

func main() {

// Now we can do:

co := Container{Fooer: TheRealFoo{}}

sink(co)

}

This will print sink: TheRealFoo Foo.

What’s going on? Notice how the Container is initialized; the embedded Fooer field gets assigned a value of type TheRealFoo. We can only assign values that implement the Fooer interface to this field - any other value will be rejected by the compiler. Since the Fooer interface is embedded in Container, its methods are promoted to be Container’s methods, which makes Container implement the Fooer interface as well! This is why we can pass a Container to sink at all; without the embedding, sink(co) would not compile because co wouldn’t implement Fooer.

You may wonder what happens if the embedded Fooer field of Container is not initialized; this is a great question! What happens is pretty much what you’d expect - the field retains its default value, which in the case of an interface is nil. So this code:

co := Container{}

sink(co)

Would result in a runtime error: invalid memory address or nil pointer dereference.