Go Notes of Function, Method and Interface (3)

A function is a group of statements that perform a specific task. In GO functions are first-order variables. They can be passed around like any other variable. A method in golang is nothing but a function with a receiver. A receiver is an instance of some specific type such as struct, but it can be an instance of any other custom type. Interface is a type in Go which is a collection of method signatures.

Function

Defination

A function is a group of statements that perform a specific task. In GO functions are first-order variables. They can be passed around like any other variable.

Some point worth noting about a function name

-

A function name cannot begin with a number

-

The function name is case sensitive. Hence sum, Sum, SUM are different functions.

-

A function whose name starts with a capital letter will be exported outside its package and can be called from other packages. A function whose name starts with lowercase letters will not be exported and it’s only visible within its package.

Signature of a function

func func_name(input_parameters) return_values{

//body

}

func sum(a int, b int) int {

return a + b

}

A function in golang

-

Declared using func keyword

-

It has a name

-

Comma-separated zero or more input parameters

-

Comma-separated zero or more return values

-

Function body

-

Can return multiple values

Some points to note about calling a function

-

If the function of some other package is being called then it is necessary to prefix the package name. Also please note that across packages only those function can be called which are exported meaning whose name start with capital letter

-

With in the same package the function can directly be called using its name suffixed by ()

Function Usages

-

Generic usage

-

Function as Type

-

Function as Values

The difference between function as type and function as values is that in type we only use the function signature whereas in function as value signature along with the body is used.

Function as Type

In go function is also a type. Two function will be of same type if

-

They have the same number of arguments with each argument is of the same type

-

They have same number of return values and each return value is of same type.

Function type is useful in

-

In the case of higher-order functions as we have seen in the above example. The argument and return type is specified using function type

-

In the case of defining interfaces in go as in the interface, only the function type is specified. Whatever implements this interface has to define a function of the same type

Function as User Defined Type

Function as user defined type can be declared using the type keyword

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

areaF := getAreaFunc()

print(3, 4, areaF)

}

type area func(int, int) int

func print(x, y int, a area) {

fmt.Printf("Area is: %d\n", a(x, y))

}

func getAreaFunc() area {

return func(x, y int) int {

return x * y

}

}

Function as values (or Anonymous functions)

A function in Go is a first-order variable so it can be used as a value as well. It is also called as anonymous functions because a function is not named and can be assigned to a variable and passed around.

They are generally created for short term use or for limited functionality.

Special Usages of Function

Function Closures

Function closures are nothing but anonymous function which can access variables declared outside the function and also retain the current value between different function calls.

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func main() {

modulus := getModulus()

modulus(-1)

modulus(2)

modulus(-5)

}

func getModulus() func(int) int {

count := 0

return func(x int) int {

count = count + 1

fmt.Printf("modulus function called %d times\n", count)

if x < 0 {

x = x * -1

}

return x

}

}

Higher Order Function

Higher-order functions are those functions that either accept a function as a type or return function. Since the function is the first-order variable in Golang they can be passed around and also returned from some function and assigned to a variable.

-

print function takes a function of type func(int, int) int as an argument

-

getAreafunc returns a function of type func(int, int) int

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

areaF := getAreaFunc()

print(3, 4, areaF)

}

func print(x, y int, area func(int, int) int) {

fmt.Printf("Area is: %d\n", area(x, y))

}

func getAreaFunc() func(int, int) int {

return func(x, y int) int {

return x * y

}

}

IIF or Immediately Invoked Function

IIF or Immediately Invoked Function are those function which can be defined and executed at the same time.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

squareOf2 := func() int {

return 2 * 2

}()

fmt.Println(squareOf2)

}

Use Cases of IIF functions

- When you don’t want to expose the logic of the function either within or outside the package. For eg let’s say there is a function which is setting some value. You can encapsulate all the logic of setting in an IIF function. This function won’t be available for calling either outside or within the package.

Variadic Function

In Go, a function that can accept a dynamic number of arguments is called a Variadic function. Below is the syntax for variadic function. Three dots are used as a prefix before type.

// func add(numbers ...int)

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

fmt.Println(add(1, 2))

fmt.Println(add(1, 2, 3))

fmt.Println(add(1, 2, 3, 4))

}

func add(numbers ...int) int {

sum := 0

for _, num := range numbers {

sum += num

}

return sum

}

Methods

Defination

A method in golang is nothing but a function with a receiver. A receiver is an instance of some specific type such as struct, but it can be an instance of any other custom type. So basically when you attach a function to a type, then that function becomes a method for that type. The method will have access to the properties of the receiver and can call the receiver’s other methods.

Method has a receiver argument. When you attach a function to a type, then that function becomes a method for that type. A receiver can be a struct or any other type. The method will have access to the properties of the receiver and can call the receiver’s other methods.

Why Method

Since method lets you define a function on a type, it lets you write object-oriented code in Golang. There are also some other benefits such as two different methods can have the same name in the same package which is not possible with functions

Format of a Method

func (receiver receiver_type) some_func_name(arguments) return_values

Function

func some_func_name(arguments) return_values

Method

func (receiver receiver_type) some_func_name(arguments) return_values

This is the only difference between function and method, but due to it they differ in terms of functionality they offer

-

A function can be used as first-order objects and can be passed around while methods cannot.

-

Methods can be used for chaining on the receiver while function cannot be used for the same.

-

There can exist different methods with the same name with a different receiver, but there cannot exist two different functions with the same name in the same package.

Methods on Structs

Golang is not an object-oriented language. It doesn’t support type inheritance, but it does allow us to define methods on any custom type including structs. Since struct is a named collection of fields and methods can also be defined on it. As such struct in golang can be compared to a class in Object-Oriented Languages.

package main

import "fmt"

type employee struct {

name string

age int

salary int

}

func (e employee) details() {

fmt.Printf("Name: %s\n", e.name)

fmt.Printf("Age: %d\n", e.age)

}

func (e employee) getSalary() int {

return e.salary

}

func main() {

emp := employee{name: "Sam", age: 31, salary: 2000}

emp.details()

fmt.Printf("Salary %d\n", emp.getSalary())

}

Since the method is defined on a value receiver when the method is called a copy of the receiver is made and that copy of the receiver is available inside the method. Since it is a copy, any changes made to the value receiver is not visible to the caller. That is why it prints the old name “Sam” instead of “John”. Now the question which comes to the mind whether there is any way to fix this. And the answer is yes, and this is where pointer receivers come into the picture.

Method on a Pointer Receiver

package main

import "fmt"

type employee struct {

name string

age int

salary int

}

func (e *employee) setNewName(newName string) {

e.name = newName

}

func main() {

emp := &employee{name: "Sam", age: 31, salary: 2000}

emp.setNewName("John")

fmt.Printf("Name: %s\n", emp.name)

}

Is it necessary to create the employee pointer to call a method with a pointer receiver? No, it is not. The method can be called on the employee instance and the language will take care of it to correctly pass it as a pointer to the method. This flexibility is provided by the language.

To summarize what we learnt above

-

If a method has a value receiver it supports calling of that method with both value and pointer receiver

-

If a method has a pointer receiver then also it supports calling of that method with both value and pointer receiver

This is unlike function where if

-

If a function has a pointer argument then it will only accept a pointer as an argument

-

If a function has a value argument then it will only accept a value as an argument

When to use pointer receiver

-

When the changes to the receiver made inside the method have to be visible to the caller.

-

When the struct is big, then it is better to use a pointer receiver otherwise a copy of the struct will be made every time a method is called which will be expensive

Some More Points to note about methods

- The receiver type has to be defined in the same package as the method definition. On defining a method on a receiver that exists in a different package, below error will be raised.

ERROR: cannot define new methods on non-local types

- Till now we have seen a method invocation using a dot operator. There is one other way to call a method as well as shown in below example

package main

import "fmt"

type employee struct {

name string

age int

salary int

}

func (e employee) details() {

fmt.Printf("Name: %s\n", e.name)

fmt.Printf("Age: %d\n", e.age)

}

func (e *employee) setName(newName string) {

e.name = newName

}

func main() {

emp := employee{name: "Sam", age: 31, salary: 2000}

employee.details(emp)

(*employee).setName(&emp, "John")

fmt.Printf("Name: %s\n", emp.name)

}

In above example we see a different method for calling a method. There are two cases

- When the method has a value receiver then it can be called as below which is struct name followed by method name. The first argument is the value receiver itself.

employee.details(emp)

- When the method has a pointer receiver then it can be called as below which is a pointer to struct name followed by method name. The first argument is the pointer receiver.

(*employee).setName(&emp, "John")

Method Chaining

For method chaining to be possible the methods in the chain should return the receiver. Returning the receiver for the last method inn the chain is optional.

package main

import "fmt"

type employee struct {

name string

age int

salary int

}

func (e employee) printName() employee {

fmt.Printf("Name: %s\n", e.name)

return e

}

func (e employee) printAge() employee {

fmt.Printf("Age: %d\n", e.age)

return e

}

func (e employee) printSalary() {

fmt.Printf("Salary: %d\n", e.salary)

}

func main() {

emp := employee{name: "Sam", age: 31, salary: 2000}

emp.printName().printAge().printSalary()

}

Methods on Non-Struct Types

Methods can also be defined on a non-struct custom type. Non-struct custom types can be created through type definition. Below is the format for creating a new custom type

type {type_name} {built_in_type}

type myFloat float64

Interface

Defination

Interface is a type in Go which is a collection of method signatures. These collections of method signatures are meant to represent certain behaviour. The interface declares only the method set and any type which implements all methods of the interface is of that interface type.

Interface lets you use duck typing in golang. Now, what is duck typing?

Duck typing is a way in computer programming which lets you do duck test where we do not check type instead we check the only presence of some attributes or methods. So what really matters is whether an object has certain attributes and methods and not its type.

Duck typing comes from the below phrase

If it walks like a duck and quack like a duck then it must be duck

Coming back to interface again. So what is interface? As mentioned before also it is a collection of method signatures. It defines the exact set of methods that a type might have. Below is the signature of an interface, it has only method signatures

type name_of_interface interface{

//Method signature 1

//Method signature 2

}

A method signature would include

-

Name of the method

-

Number of arguments and type of each argument

-

Number of return values and type of each return value

Implementing an Interface

Any type which implements the breathe and walk method then it is said to implement the animal interface. So if we define a lion struct and implements the breathe and walk method then it will implement the animal interface.

package main

import "fmt"

type animal interface {

breathe()

walk()

}

type lion struct {

age int

}

func (l lion) breathe() {

fmt.Println("Lion breathes")

}

func (l lion) walk() {

fmt.Println("Lion walk")

}

func main() {

var a animal

a = lion{age: 10}

a.breathe()

a.walk()

}

If you notice that there is no explicit declaration that the lion type implements the animal interface. This brings a very important property related to interface – ‘Interface are implemented implicitly

Interface are implemented implicitly

There is no explicit declaration that a type implements an interface. In fact, in Go there doesn’t exist any “implements” keyword similar to Java. A type implements an interface if it implements all the methods of the interface.

As seen above, It is correct to define a variable of an interface type and we can assign any concrete type value to this variable if the concrete type implements all the methods of the interface.

There is no explicit declaration that says that lion struct implements the animal interface. During compilation, go notices that lion struct implements all methods of animal interface hence it is allowed. Any other type which implements all methods of the animal interface becomes of that interface type.

Two important points to note:

- The interface static check is done during compile time – means that if a type doesn’t implement all the methods of an interface, then assigning the type instance to a variable of that interface type will raise an error during compile time. Eg. on deleting the walk method defined on lion struct, below error will be raised during the assignment

cannot use lion literal (type lion) as type animal in assignment:

- The correct method based on the type of instance is called at run time – means that the method of either lion or dog is called depending upon whether interface variable refers to an instance of lion or dog. If it refers to an instance of lion, then lion’s method is called and if it refers to an instance of dog, then dog’s method is called. That is also proven from the output. This is a way to achieve runtime polymorphism in Go.

It is also to be noted that the methods defined by the type, should match the entire signature of methods in the interface ie., it should match

-

Name of the method

-

Number of arguments and type of each argument

-

Number of return values and type of each return value

Interface types as argument to a function

A function can accept an argument of an interface type. Any type which implements that interface can be passed as that argument to that function. For example, in the below code, we have callBreathe and callWalk function which accept an argument of animal interface type. Both lion and dog instance can be passed to this function. We create an instance of both lion and dog type and pass it to the function.

It works similarly to the assignment we discussed above. During compilation no type is checked while calling the function, instead, it is enough to check that the type passed to the function does implement breathe and walk method.

package main

import "fmt"

type animal interface {

breathe()

walk()

}

type lion struct {

age int

}

func (l lion) breathe() {

fmt.Println("Lion breathes")

}

func (l lion) walk() {

fmt.Println("Lion walk")

}

type dog struct {

age int

}

func (l dog) breathe() {

fmt.Println("Dog breathes")

}

func (l dog) walk() {

fmt.Println("Dog walk")

}

func main() {

l := lion{age: 10}

callBreathe(l)

callWalk(l)

d := dog{age: 5}

callBreathe(d)

callWalk(d)

}

func callBreathe(a animal) {

a.breathe()

}

func callWalk(a animal) {

a.breathe()

}

Why Interface

Below are some benefits of using interface.

- Helps write more modular and decoupled code between different parts of codebase – It can help reduce dependency between different parts of codebase and provide loose coupling.

For eg imagine an application interacting with a database layer. If the application interacts with the database using the interface, then it never gets to know about what kind of database is being used in the background. You can change the type of database in the background, let’s say from arango db to mongo db without any change in the application layer as it interacts with the database layer via an interface which both arango db and mongo db implement.

- Interface can be used to achieve run time polymorphism in golang. RunTime Polymorphism means that a call is resolved at runtime. Let’s understand how interface can be used to achieve runtime polymorphism with an example

Different countries have different ways of calculating the tax. This can be represented by means of an interface.

type taxCalculator interface{

calculateTax()

}

Non-struct Custom Type Implementing an interface

So far we have only seen examples of struct type implementing an interface. It is also perfectly ok for any non-struct custom type to implement an interface. Let’s see an example

package main

import "fmt"

type animal interface {

breathe()

walk()

}

type cat string

func (c cat) breathe() {

fmt.Println("Cat breathes")

}

func (c cat) walk() {

fmt.Println("Cat walk")

}

func main() {

var a animal

a = cat("smokey")

a.breathe()

a.walk()

}

The above program illustrates the concept that any custom type can also implement an interface. The cat is of string type and it implements the breathe and walk method hence it is correct to assign an instance of cat type to a variable of animal type

Type Implementing multiple interfaces

A type implements an interface if it defines all methods of an interface. If that defines all methods of another interface then it implements that interface. In essence, a type can implement multiple interfaces.

package main

import "fmt"

type animal interface {

breathe()

walk()

}

type mammal interface {

feed()

}

type lion struct {

age int

}

func (l lion) breathe() {

fmt.Println("Lion breathes")

}

func (l lion) walk() {

fmt.Println("Lion walk")

}

func (l lion) feed() {

fmt.Println("Lion feeds young")

}

func main() {

var a animal

l := lion{}

a = l

a.breathe()

a.walk()

var m mammal

m = l

m.feed()

}

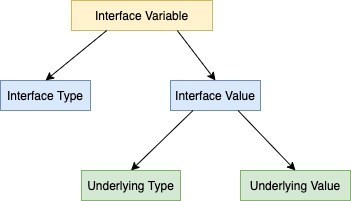

Inner Working of Interface

Like any other variable, an interface variable is represented by a type and value. Interface value, in turn under the hood, consists of two tuple

-

Underlying Type

-

Underlying Value

See below diagram which illustrates what we mentioned above

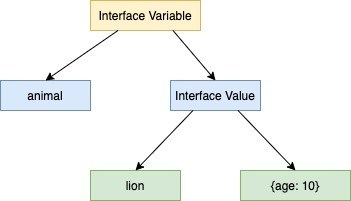

For eg in case of lion struct implementing the animal interface would be like below

Golang provides format identifiers to print the underlying type and underlying value represented by the interface value.

-

%T can be used to print the concrete type of the interface value

-

%v can be used to print the concrete value of the interface value.

package main

import "fmt"

type animal interface {

breathe()

walk()

}

type lion struct {

age int

}

func (l lion) breathe() {

fmt.Println("Lion breathes")

}

func (l lion) walk() {

fmt.Println("Lion walk")

}

func main() {

var a animal

a = lion{age: 10}

fmt.Printf("Underlying Type: %T\n", a)

fmt.Printf("Underlying Value: %v\n", a)

}

Embedding Interfaces

An interface can be embedded in other interface as well as it can be embedded in a struct. Let’s look at each one by one

Embedding interface in other interface

An interface can embed any number of interfaces in it as well as it can be embedded in any interface. All the methods of the embedded interface become part of the embedding interface. It is a way of creating a new interface by merging some small interfaces. Let’s understand it with an example

type animal interface {

breathe()

walk()

}

Let’s say there is another interface named human which embeds the animal interface

type human interface {

animal

speak()

}

So if any type needs to implement the human interface, then it has to define

-

breathe() and walk() method of animal interfaces animal is embedded in human

-

speak() method of human interface

package main

import "fmt"

type animal interface {

breathe()

walk()

}

type human interface {

animal

speak()

}

type employee struct {

name string

}

func (e employee) breathe() {

fmt.Println("Employee breathes")

}

func (e employee) walk() {

fmt.Println("Employee walk")

}

func (e employee) speak() {

fmt.Println("Employee speaks")

}

func main() {

var h human

h = employee{name: "John"}

h.breathe()

h.walk()

h.speak()

}

Embedding interface in a struct

An interface can be embedded in a struct as well. All the methods of the embedded interface can be called via that struct. How these methods will be called will depend upon whether the embedded interface is a named field or an unnamed/anonymous field.

-

If the embedded interface is a named field, then interface methods has to be called via the named interface name

-

If the embedded interface is unnamed/anonymous field then interface methods can be referred directly or via the interface name

package main

import "fmt"

type animal interface {

breathe()

walk()

}

type dog struct {

age int

}

func (d dog) breathe() {

fmt.Println("Dog breathes")

}

func (d dog) walk() {

fmt.Println("Dog walk")

}

type pet1 struct {

a animal

name string

}

type pet2 struct {

animal

name string

}

func main() {

d := dog{age: 5}

p1 := pet1{name: "Milo", a: d}

fmt.Println(p1.name)

// p1.breathe()

// p1.walk()

p1.a.breathe()

p1.a.walk()

p2 := pet2{name: "Oscar", animal: d}

fmt.Println(p1.name)

p2.breathe()

p2.walk()

p1.a.breathe()

p1.a.walk()

}

Access Underlying Variable of Interface

The underlying variable can be accessed in two ways

-

Type Assertion

-

Type Switch

Type Assertion

Type assertion provides a way to access the underlying variable inside the interface value of the interface by asserting the correct type of underlying value. Below is the syntax for that where i is an interface.

val := i.({type})

package main

import "fmt"

type animal interface {

breathe()

walk()

}

type lion struct {

age int

}

func (l lion) breathe() {

fmt.Println("Lion breathes")

}

func (l lion) walk() {

fmt.Println("Lion walk")

}

type dog struct {

age int

}

func (d dog) breathe() {

fmt.Println("Dog breathes")

}

func (d dog) walk() {

fmt.Println("Dog walk")

}

func main() {

var a animal

a = lion{age: 10}

print(a)

}

func print(a animal) {

l := a.(lion)

fmt.Printf("Age: %d\n", l.age)

//d := a.(dog)

//fmt.Printf("Age: %d\n", d.age)

}

Type Switch

Type switch enables us to do above type assertion in series.

package main

import "fmt"

type animal interface {

breathe()

walk()

}

type lion struct {

age int

}

func (l lion) breathe() {

fmt.Println("Lion breathes")

}

func (l lion) walk() {

fmt.Println("Lion walk")

}

type dog struct {

age int

}

func (d dog) breathe() {

fmt.Println("Dog breathes")

}

func (d dog) walk() {

fmt.Println("Dog walk")

}

func main() {

var a animal

x = lion{age: 10}

print(x)

}

func print(a animal) {

switch v := x.(type) {

case lion:

fmt.Println("Type: lion")

case dog:

fmt.Println("Type: dog")

default:

fmt.Printf("Unknown Type %T", v)

}

}

Empty interface

An empty interface has no methods , hence by default all concrete types implement the empty interface. If you write a function that accepts an empty interface then you can pass any type to that function.